Sorry, this entry is only available in العربية, Español, Italiano and Français.

Nov 24 2012

Church and Catholicism since 1945 in the Near East and North Africa

Harald Suermann (Hg.), Naher Osten und Nordafrika = Erwin Gatz (Hg.), Kirche und Katholizismus seit 1945, Paderborn, 2010, XX, 255 S.; ISBN: 978-3-506-74465-4

This volume presents the development of the various Catholic churches in the Middle East and North Africa since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire until today. In the Maghreb countries, where there is practically only the Roman Catholic tradition, particular attention is given to the transition of the church from the colonial power to the churches of the independent states.

As regards the various Catholic churches in the Middle East – Coptic Catholic, Armenian Catholic, Syrian Catholic, Greek Catholic, Chaldean, Maronite and Latin (Roman) – the diversity of traditions and history of multiple branches are represented. Items of each country (Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Holy Land, Egypt, North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula ) portray the history of each of the churches. Emigration and immigration are treated as well as inter-religious and ecumenical dialogue. Institutions such as the episcopal conferences and caritas are subject, as well as Catholic schools and the relationship between church and state . Refugees find a place as well as the sociological profile of Christians.

The churches of the Arabian Peninsula formed mainly of migrant workers in the West and Asia are also described.

Contents

Foreword V

Table of Contents VII

List of abbreviations XV

Glossary XVII

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

By Harald Suermann 1

1. The general situation in the Middle East and North Africa 1

2. The individual churches 2

3. History of Christians in Islamic countries 8

4. The common institutions and ecumenism 10

4.1. Middle East Concil of Churches 12

4.2 . The Catholic-Orthodox dialogue 15

4.3. Oriental Churches and the Latin Church 18

a) the first phase 19

b) The second phase 20

c ) The third phase 20

4.4. The Catholic-Assyrian dialogue 22

5. The common Catholic institutions 27

5.1. Council of the Catholic Patriarchs of the Orient 27

5.2 . CELRA and C. E. R. N. A. 29

5.3 . Special meetings of the Synod of Bishops 30

6. Inter-religious dialogue 30

7. Migration 32

CHAPTER 2: Turkey

By Herman Teule 35

1. The inter-war period 36

2. The ecclesiastical structure in the postwar period 38

2.1. Emigration and related developments 40

2.2. The Chaldean Church 40

2.3. The Syrian Catholic and Syrian Orthodox churches 42

2.4. The Gregorian ( Orthodox ) Armenian and Armenian Catholics 43

2.5. The Greek Orthodoxes and the Greek Catholics 44

3. Inculturation 46

4. Ecumenism 48

5. Dialogue with Islam – Position of Christian minorities 49

6. Contacts with the authorities and legal status of churches 50

7. Conclusion 51

CHAPTER 3: Iraq

By Harald Suermann 53

1. The churches and their origins in Iraq 53

2. Churches in particular 54

2.1. The Catholic Particular Churches 54

2.2 . The non-Catholic churches 56

-

Ottoman Empire – Independence (1932) – Hashemite monarchy (1921-1958) 57

3.1. Mandate 58

3.2. The Hashemite monarchy 59

3.3. The Republic of 1958-1968 60

4. From 1968 up to the First Gulf War 63

5. From the Second to the Third Gulf War (1990-2003) 68

6. Third Gulf War 72

6.1. Criticism of the Christians and their position before the Third Gulf War 72

6.2 . The invasion and occupation of Iraq 74

7. The post-war period 75

7.1. The Christians and the new Constitution 76

7.2 . The Iraqi interim constitution 77

7.3. The elections of January 30th, 2005 77

7.4. The new constitution 78

7.5. The general situation of Christians 80

7.6. The situaltion in the south 84

7.7. The situation in the north 84

CHAPTER 4 : Syria

By Herman Teule 87

1. Introduction 87

2. Inter-war period 88

2.1. Nationalism 88

2.2. The Christian population on the eve of independence 89

3. The Catholic communities after independence 91

3.1. The organization 91

3.2 . Ecumenism 94

3.3. Second Vatican Ecumenical Council 98

3.4. Relations with Islam 99

3.5. The school question 100

3.6. Emigration and immigration 102

4. Some recent significant events 104

CHAPTER 5 : Lebanon

By Harald Suermann 105

1. The different denominations 105

1.1. The Catholic particular Churches 105

a) Maronites 105

b) The Melkite or Greek Catholic 108

c) The Syriac Catholic 109

d) The Chaldeans 109

e) The Armenian Catholic 109

f) The Latins 110

1.2. The Orthodox and Protestants 111

a) The Greek Orthodox (Rum Orthodox) 111

aa) church structure 112

ab) The Orthodox Youth Movement 112

b) The Syriac Orthodox 113

c) The Armenian Orthodox 113

d) The Protestants 113

2. Assemblée des Catholiques au Liban Patriarches et Evêques (APECL) 114

3. History 114

3.1. Lebanon at the end of the Ottoman period 114

3.2. The independent Lebanon 116

a) The National Pact and the proportional representation 116

b) The development of denominations and church structures 119

3.3. From independence until the Civil War 120

3.4. The Civil War 124

a) The first phase 124

b) The second phase 125

c) southern Lebanon 127

3.5. From the Civil War to the Special Synod for Lebanon 128

3.6. Special Assembly of the Synod of Bishops for Lebanon 129

3.7. Further development 132

CHAPTER 6 : Jordan

By Harald Suermann 137

1. The different Churches 137

1.1. The Catholic particular Churches 137

1.2. The Orthodox and Protestants 138

2. Form of government 138

2.1. The tribal structure of the Jordanian Christians 139

2.2 . The Palestinian Christians 140

3. History 140

4. Inter-religious Relations 143

5. Ecumenism 144

6. Social Organization 144

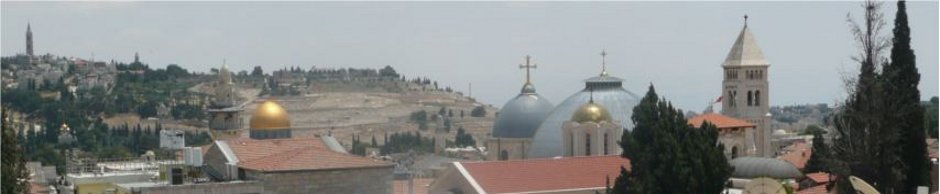

CHAPTER 7 : The Holy Land

By Rainer Zimmer-Winkel 147

1. Introduction 147

2. The time until 1917 147

3. British rule in Palestine. Period of military rule (1917-20), time of the League of Nations mandate (1920-48 ) 150

4. The caesura 1947-48 152

5. The ecclesiastical situation since 1948 154

5.1. Development until 1967 154

5.2. Situation after 1967 155

5.3 . The visits of Paul VI (1964), John Paul II (2000) and Benedict XVI ( 2009) 156

6. The ecumenical situation in Jerusalem 157

7. The Catholic organization structure in the Holy Land 159

7.1. Roman Catholic institutions 159

a) The Catholic Ordinarienversammlung (Assembly of Catholic Ordinaries of the Holy Land, AOCTS ) 159

b) The Latin Patriarchate 160

c) The Hebrew-speaking Catholics 161

d) Custodia Terrae Sanctae – The Custody of the Holy Land (Franciscans) 161

7.2 . The rite churches in communion with Rome 162

a) The Melkites 162

b) The Maronites 163

c) The Armenian Catholic Church 163

d) Syrian Catholic Church 163

e) The Chaldean and the Coptic Catholic Church 163

f) The Apostolic Nunciature in Israel 164

g) The Apostolic Delegation in Jerusalem and Palestine 164

7.3. Works and facilities 164

a) Caritas 165

b) Ecce Homo – Center for Biblical Formation 165

c) École Biblique 166

d) Justice and Peace Commission 166

e) Notre Dame de Jérusalem 166

f) Ecumenical Institute for Theological Studies Tantur 167

g) Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem

(Ordo Sancti Equestris Sepulchri Hierosolymitani) 167

h) Pontifical Mission for Palestine 168

i) Pontifical Biblical Institute 168

j) Religious and Heritage Studies in the Holy Land – Al- Liqa Center 168

k) Rosary Sisters 169

l) Faculty of Biblical Sciences and Archaeology 169

m) Bethlehem University 169

n) White Fathers (St. Anna ) – Biblical and Renewal Center 170

7.4. Church press and public relations 170

a) The Diocesan Bulletin 170

b) Associated Christian Press Bulletin 171

c) Proche-Orient Chrétien 171

d) Holy Land – Illustrated Quarterly of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land 171

e) Christian Information Centre – Franciscan Pilgrims ‘ Office 171

f) Holy Land Catholic Communications Centre 171

7.5. Palestinian theology 172

8. Concluding remarks 173

CHAPTER 8 : Arabian Peninsula ( The Apostolic Vicariate of Arabia

and the Vicariate Apostolic of Kuwait)

By Harald Suermann 175

1. History 175

2. Bahrain 179

3. Qatar 180

4. United Arab Emirates 180

4.1. Abu Dhabi 180

4.2 . Dubai 181

4.3. Sharja 181

5. Oman 181

6. Saudi Arabia 182

7. Apostolic Vicariate of Kuwait 184

CHAPTER 9 : Egypt

By Harald Suerman 185

1. Figures and churches 185

2. Form of government 186

2.1. History 186

2.2 . Sociology 190

2.3. Constitution 190

3. Social positions of Christians 192

3.1. Christian-Muslim relations 194

3.2 . Dialogue 198

4. The individual churches 199

4.1. The Coptic Orthodox Church 199

4.2 . The Greek Orthodox Church of the Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Afric 201

4.3. The Greek Orthodox autocephalous Archdiocese of Saint Catherine, Sinaï 201

4.4. The Armenian Orthodox Church 201

4.5. The Syrian Orthodox Church 202

4.6. The Episcopal Church 202

4.7. The Protestant churches 202

4.8. The Catholic particular Churches 202

a) The Latin Church 203

b) The Coptic Catholic Church 204

c) The remaining part of Catholic churches 205

d) The Catholic community facilities 206

5. Ecumenism 207

CHAPTER 10 : Maghreb

By Harald Suerman 211

1. Common characteristics 212

2. Libya 214

2.1. The colonial era 214

2.2. The independent Libya 215

3. Tunisia 216

3.1. The colonial era 217

3.2. The end of the colonial period 218

3.3. The church in independent Tunisia 220

4. Algeria 221

4.1. The colonial heritage 222

4.2. The period of the Republic 224

4.3. The crisis of Algerian society from 1992 to 1998 226

4.4. The period since 1998 228

5. Morocco 229

5.1. The colonial era 230

5.2 . The independent kingdom 231

CHAPTER 11 : Conclusions

By Harald Suermann 235

Register 243

1. Name register 243

2. Location register 247

3. Subject index 251

Authors 255

Nov 24 2012

Fiona McCallum, Christian Religious Leadership in the Middle East.

Fiona McCallum, Christian Religious Leadership in the Middle East. The political role of the Patriarch. With a Foreword by John Anderson and Raymond Hinnebusch, Lewiston 2010; ISBN 978-0-7734-3794-3; VI+298 pp.

This publication is a revised version of a PhD-Thesis presented in 2006 at the University of St. Andrew in Scotland. It deals with the political dimension of the two important patriarchates in the Middle East and the development of the political power of the two contemporary Patriarchs: Pope Shenuda III (coptic-orthodox) and the Patriarch Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir (maronite). At the beginning there are four theoretical models which attempt to explain the relation between the a specific shaping of a state and the political power of religious institutions. The author identifies 8 variables to analyse the contemporary political dimension of the given patriarchate and its recent development. These variables are centred around the relation of the community and the patriarch, only one variable concerns the political situation of the country. The identification of the variables indicates that the research concerns specifically the political power over their respective community.

This kind of approach to modern reality of the Christian communities in the Middle East is still rare in Western modern research. But it can help much to better understand the political situation of these small communities.

The nest pages (41-98) gives a summary of what is known about the history and the modern development. Starting in Chapter 4 (123) the kernel of the thesis is worked out. It is a detailed analysis of the political role of the two patriarchs and how it changed during history. The author is presenting many aspects and incidents concerning the modern history. She analysis also the important aspect between lay people and the patriarch and hierarchy. Some of these groups are challenging the political role of the patriarch.

In the conclusion the thesis presented in the first chapter are verified on the basis of the realized analysis.

The approach and the methods are good however the thesis has some mistakes and grave defects. A wrong citation, misspelling of names, or mistake like the identification of didaskalia as a catechetical school are found the publication. However the biggest defect is the total ignorance of literature which is not in English. The author does not use any Arab source. In Egypt she had the advantage that quite a number are translated into English by the Arab-West-Report. She mentions some French books in the bibliography, however from the citation on gain the impression that they are secondary citations. Concerning Lebanon she relays on one of the less important but English paper: The daily Star. For this subject it is imperative to consult L’Orient-Le jour, An-Nahar and As-Safir. Ignoring German, Spanish, and Italian publications would been pardonable. But ignoring the Arabic and for Lebanon French sources – journals as well as scientific literature – reduces considerably the quality of the work.

Harald Suermann

(A longer review of the work will be published in Oriens Christianus 94, 2010, 275-279)

Apr 18 2011

(Deutsch) Christen in Tunesien

Mar 23 2011

Christen in Libyen

Libya has 6.4 million inhabitants, including about 75,000 Catholics. Most of them live in the Apostolic Vicariate of Tripoli, much less belong to the Apostolic Vicariate of Benghazi. The Apostolic Vicariate of Derna has been vacant since 1948, as well as the Apostolic Prefecture of Misurata has been vacant sinc 1969.

After the revolution in September 1969 an agreement between the Holy See and the Libyan government was signed on October 10th, 1970. The church property was nationalized, two church buildings were left to the Catholic Church for use. The maximum number of priests, who were permitted to operate in the state, was ten. However, hundreds of nurses were recruited for the hospital service.

The colonial era

After Italian troops had occupied the coastal cities of Libya, Mgr Antonnelli came to Libya in 1911 and established the Apostolic Vicariate of Libya on February 23rd, 1913. His successor, P. Tonizza took care of the infrastructure and built a cathedral, kindergartens, schools and parish centers. In 1927, the Apostolic Vicariate was split into the two vicariates of Tripoli and Benghazi in the Cyrenaica. Although the church had to look after the Italian soldiers during the occupation, she cultivated very good relations with the Muslim population.

The independent Libya

In 1951, Libya became independent and formed a constitutional monarchy under King Idris al-Sanussi.

On September 1st, 1969 Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi came to power. On July 21st, 1970, he announced the confiscation of the goods of the Italians and their expulsion, which were completed by September of the year. The church was affected by this act. After tough negotiations, six priests could stay in Tripoli and Benghazi, they were allowed to celebrate their liturgy. Most of the churches were closed, although the Constitution to guarantee freedom of religion. The cathedral of the capital was converted into a mosque. In retrospect, this act is considered a “cleansing” of the church, which was then almost entirely Italian. Today, it is truly international.

From February 2nd to 5th, 1976, there was a conference for the Islamic-Christian dialogue in Tripoli. Following this conference the church in Benghazi returned to the Christian and a second bishop were installed. Finally, it led to the diplomatic relations with the Vatican.

In 1977, al-Qadhafi proclaimed the establishment of the Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the aftermath guest workers came from the Philippines, Poland and Korea and the church grew in number. Since 1988, Arab Christians came as worker.

In 1986, the Catholic Bishop of Tripoli, Giovanni Martinelli, was arrested along with three priests and a nun for ten days. This action is often seen as revenge for the official meeting between Pope John Paul II and the Rabbi of Rome in that year.

Later in the 80s, the relation between the Libyan state and the Holy See gradually improved, eventually diplomatic relations between Libya and the Vatican were established in 1997 and the two Apostolic Vicariate, Benghazi and Tripoli, were errected.

The state showed significantly more interest in interreligious and intercultural dialogue since 2004 and a number of events took place.

In February 2006, the church in Benghazi and the house of the Franciscans were set on fire. This was a result of the unrest that had triggered the Muhammad cartoons in Denmark.

The Church in Libya is mainly committed to social work. Various religious work in centers for the disabled, orphans and the elderly or in hospitals.

Since the riots

From January 29th to February 2nd the bishops of the North African bishops’ conference (CERNA), including the Bishops of Tripoli and Benghazi, hold a meeting in Algiers (Algeria). There they said that the Christians in the Middle East are part of the change, they do not oppose it. The protests were a sign of the desire for freedom and dignity, especially among the younger generation. The residents claim to participate in the governance of the country as citizens with full rights and responsibilities. The bishops also call for a greater respect for religious freedom in the framework of human rights. Under Gaddafi the Christians were allowed to exercise their cult. They could not only celebrate Mass in the churches, but also in private homes and businesses. Even prison chaplaincy was possible.

The Christians are concerned that with the overthrow of Gadhafi, there will be an Islamist government, which then restricts the freedoms of Christians more then before.

While most foreigners have left the country, the migrant workers from sub-Saharan Africa often face the difficulty that they have not insufficient identity documents. Many of them have sought refuge in the churches. Religious in the country attempt to assist these worker through their embassies and UNHCR. The bishops, priests and religious, with very few exceptions, remain in the country with those Christians, who can not leave it.

The church is composed exclusively of foreigners, and so their hands are tied in the conflict. She cannot interfere or take sides. Her opportunity and challenge is to stay with the defenseless ones and to show solidarity with them. In the declaration of the bishops’ conference she had expressed her political option.

Recent Comments